General information about the case study

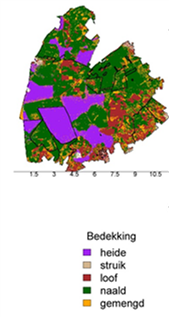

The Veluwe is an extensive forest and heathland area of 100,000 ha located in the centre of the Netherlands. The case study is located in the Southeastern part of the Veluwe and contains 8,246 ha. The area is mostly covered by forest and heathlands. In the north and central part of the area the soils are sandy and poor, while the southern edge is somewhat richer and wetter due to more loamy soils. The area has been intensively used for centuries, leading to forest degradation, conversion to heathlands and even driftsands. In the 19th and 20th century the area has been reforested, mostly with Scots pine. There are still a few areas with 200-250 year old broadleaved forest. These areas are important for nature conservation and are Natura2000 sites. Main functions of the area nowadays are recreation, nature and landscape protection, while timber production is important especially for some smaller estates. Wood production is mostly a secondary goal, but the actual mix of goals depends on the owner. All larger owners in the area have cooperated in study, together they cover 88% of the area. The high recreational pressure and the effects of (over-) grazing are the main management concerns currently. Two conservation trusts together own 75% of the area. The state forest service owns 5%, while the rest is privately owned.

Forests in the Southeast Veluwe

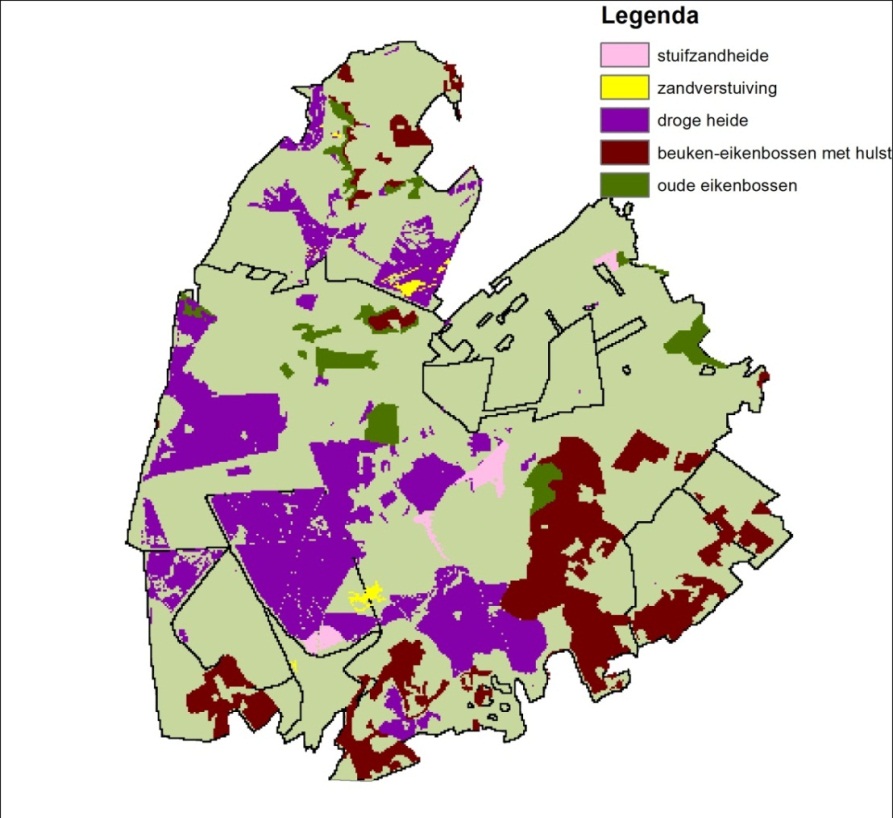

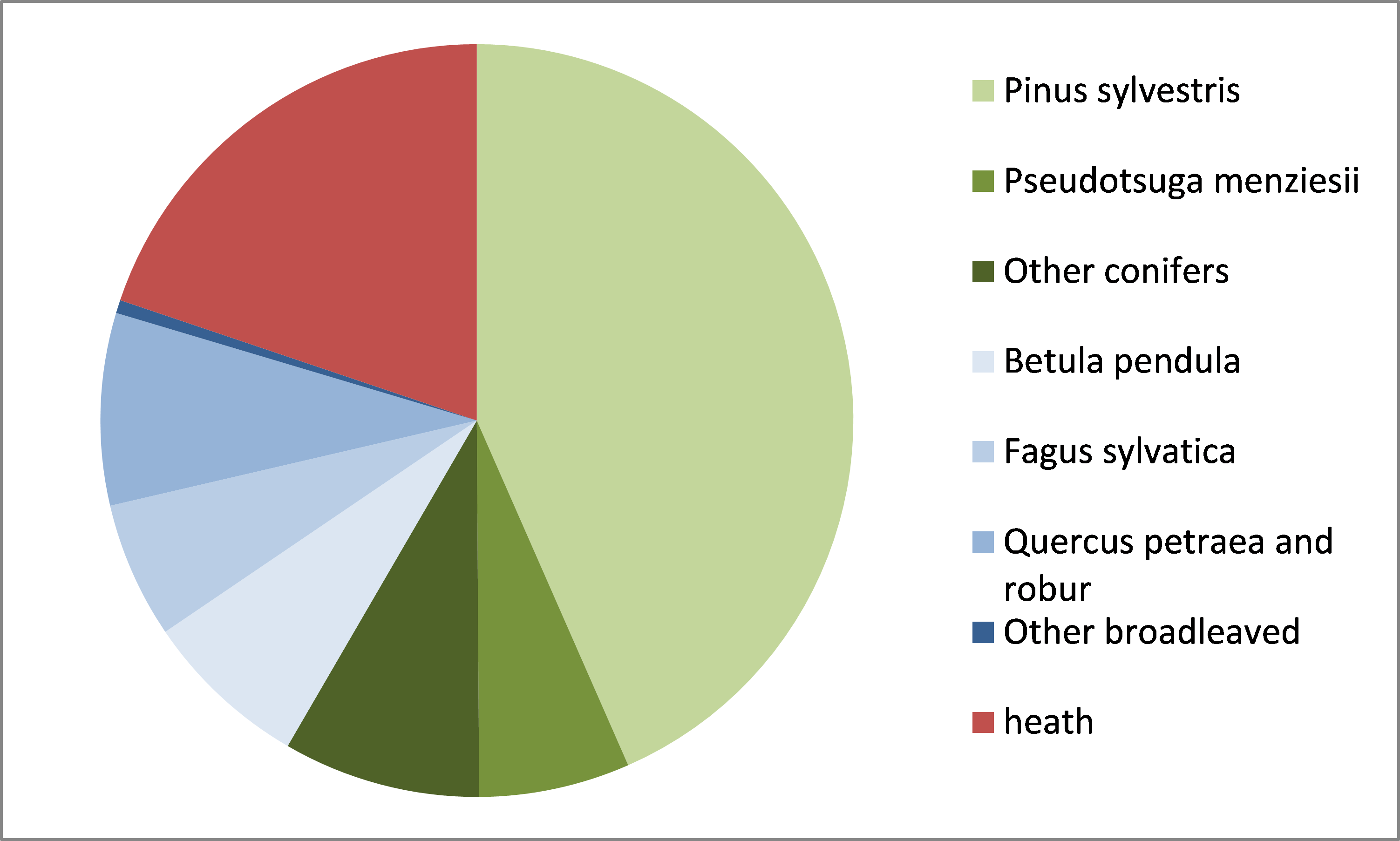

The forest is dominated by Scots pine stands, originating from the afforestation of the heathland. Some old broadleaved (oak and beech) remnants are retained in the landscape. Others have been converted to more productive coniferous species, mostly douglas fir.

Figure 3. Land cover in the case study area. Purple is heathland, red broadleaves, green conifers and yellow mixed.

Management

Different owners have different priorities in management goals, and therefore have different management regimes. The open heathlands and driftsands are very important for recreation and are generally kept open by removing invading trees. One of the trusts has a large area of forest and heathland that is grazed by bovines and no other management is applied. Also some other owners have parts of the forest that are designated as reserves. Management of most owners is characterised by aiming at increasing species mixture, limiting large-scale operations and mimicking/using natural processes.

Climate

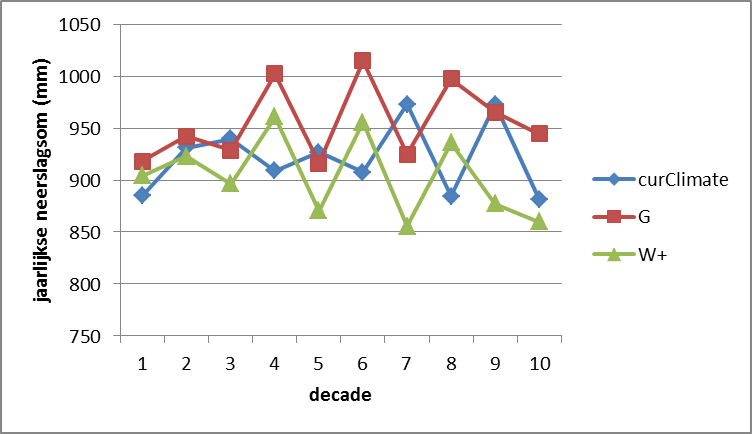

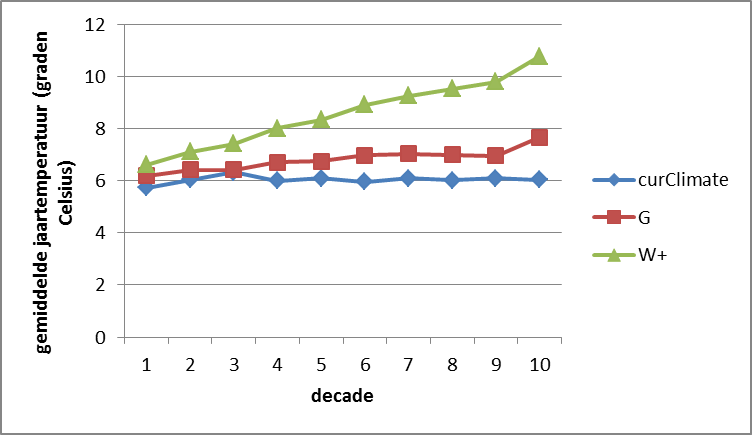

Current climate is characterised as Atlantic, with a mean annual temperature of around 6 °C and an annual precipitation of around 900mm, rather evenly distributed over the year. For the climate change scenarios, we selected the 2 extremes from the range of national climate scenarios that the Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute (KNMI) has defined. These are the scenarios G (moderate climate change: +2 °C in summer by 2100, +7% summer precipation) and W+ (more severe climate change: +4 °C by 2100 and –38% of summer precipitation due to more easterly winds).

Figure 5. Annual precipitation sum (mm), averaged per decade for the three climate scenarios. G = moderate climate change: +2 °C in summer by 2100, +7% summer precipation; W+ = more severe climate change: +4 °C by 2100 and –38% of summer precipitation due to more easterly winds.

Figure 6. Average annual temperature, averaged per decade for the three climate scenarios. G = moderate climate change: +2 °C in summer by 2100, +7% summer precipation; W+ = more severe climate change: +4 °C by 2100 and –38% of summer precipitation due to more easterly winds.

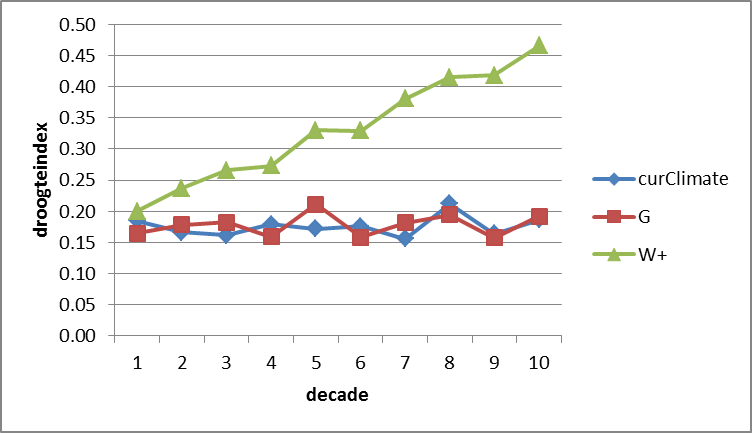

Figure 7. Drought index over the growing season as computed by the LandClim model, averaged per decade for the three climate scenarios. G = moderate climate change: +2 °C in summer by 2100, +7% summer precipation; W+ = more severe climate change: +4 °C by 2100 and –38% of summer precipitation due to more easterly winds.

Are the tree species in the forest sensitive to climate change?

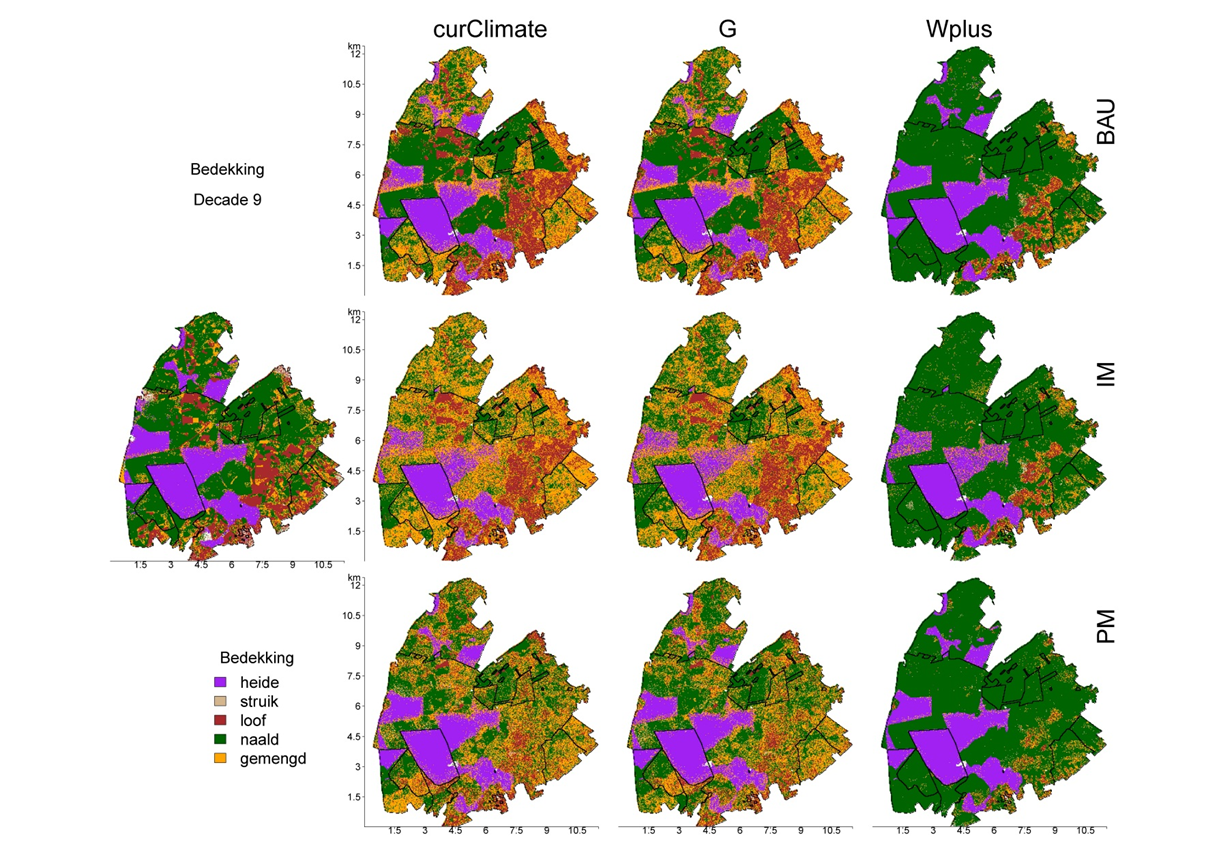

The simulated tree species distribution in 2110 (Figure VE-1) shows clear differences between current climate and moderate climate change on the one hand, and the more extreme climate change scenario on the other hand. Under current conditions or moderate climate change, beech is expected to increase in large parts of the area. However, increased drought under climate change leads to a loss of beech, in favour of drought-resistant, coniferous species, mostly Scots pine on the poor soils and Douglas fir on the somewhat richer soils. Broadleaved, drought-sensitive species like oak and beech can only maintain dominance in the south part of the area with higher water availability. The climate effect on the tree species distribution in the more extreme W+ scenario will have a larger influence on the future tree species composition than adaptive management can compensate for. Research has shown that different provenances of Douglas fir have different tolerance to drought. It is likely that such provenances have been used in our case study in the past. In the simulations we have assumed that also in future drought-tolerant varieties are used.

Will the risk profile of tree species change under climate change?

Although forest fires are relatively rare, it is considered an important risk in the area. The area is used intensively for recreation purposes and borders several densely populated urban areas. The concern with fires is thus mostly focussed on safety and economic assets rather than the forest itself. Developments towards more broadleaved tree species as found in current and moderate climate change under BAU and IM are considered as helpful to decrease the risk of fire ignition and rapid fire spread. A more extreme climate change would lead to both increased frequency of periods with high-risk weather conditions and a more vulnerable, conifer-dominated vegetation. Under the W+ scenario, maintaining a high share of broadleaves is only possible in the southern zone of the area, and management should thus focus more on managing the continuity and build-up of the fuel in the landscape. A fire risk assessment showed increased fire risk in the heathland, especially at the borders with existing forest, where natural regeneration of coniferous species (mostly Scots pine) occurs.

It is still unclear if storm frequency and intensity will change under changing climate. It is thus mostly changes in the forest structure that will influence future storm risk. The scenarios with gradual increase of broadleaves can be considered as having equal or less risk than nowadays. An increase in dominance of especially Douglas fir might lead to somewhat increased storm risk, since Douglas fir can generally attain higher heights. This is mostly in the W+ climate scenarios and the IM management scenarios. The business as usual management shows an increase in storm risk due to a relatively low management level. Insect risk is deemed highest in the W+ climate due to more drought stress on the trees.

Assume that current management (BAU) is continued: Is it possible to achieve current goals also under climate change conditions?

Current management is in many cases already well adapted to the sites and climatic conditions, and already takes into account natural developments. A mild climate change scenario can be easily dealt with in the current management schedules and is not expected to lead to problems in relation to the goals set. Most forest functions are not much affected by the climate change scenarios. However, part of the current Natura2000-labelled old-growth oak and oak-beech sites would convert to coniferous forest under the more extreme climate scenario.

Which adaptive measures appear as suitable response to the changing climate in order to sustain the provision of demanded ecosystem services? What is the recommendation to the forest manager?

We have analysed three management scenarios. Business as usual is a continuation of the current management. Intensified management (IM) anticipates at increased productivity of the forest due to climate change by intensifying the management. In IM, in some reserves wood harvest is resumed, while some heathlands are allowed to convert naturally to forest. Thinnings are aimed at increasing production of remaining trees or to stimulate regeneration of more productive/economically attractive species, sometimes assisted by planting. Precautinary management (PM) aims at decreasing risks associated with climate change. PM is more careful than IM, with more small-scale thinnings and more care to maintain tree cover. In PM managers influence tree species distribution to decrease vulnerability. Some choose for Castanea sativa and Tilia cordata, sometimes in combination with oak, beech and birch. Other managers stimulate Scots pine and Douglas fir. All management scenarios were discussed with the managers, and the adaptive scenarios thus differ in implementation and risks/chances that are dealt with.

In general, both IM and PM have a tendency to negatively influence the forest services and risk level, although at different rates under different climate scenarios. Some trade-offs are visible, for example PM negatively affects biodiversity in the area, but has a positive effect on the standing stock and increment. IM has a smaller negative impact on biodiversity goals, but is decreasing production indicators. Overall, continuing the current management seems the best option to maintain the current levels of service provisioning. Early and strong changes in management strategy as response to an expected extreme climate change might lead to irreversible losses of especially biodiversity values if climate is less extreme as expected. However, only in another 50 years starts the W+ scenario to be really different from the G scenario, which gives ample time to adapt management to observed climate change as time progresses.

Continuation of current management is therefore the best choice for the time being, but it is recommended to monitor the forest development and the climate closely in order to be able to adapt the management if necessary. However, individual owners may decide differently for their own properties, based on different preferences.

How did you come to your conclusion(s)? Which tools and methods did you employ?

The landscape model LandClim is used to investigate large-scale effects of climate change on forest stand development and to develop and evaluate adaptive forest management strategies. The model was developed to assess the importance of climatic effects, wildfire and management on historical and future forest dynamics.

We simulated in total 9 scenarios (3 climate x 3 management scenarios). The forest was initialised with data from 1980. The period 1980-2010 was simulated with management as close as possible to real management, in consultation with stakeholders/owners/managers, and by applying observed weather over this period. All scenarios are simulated for the period 2010-2110.

How do you incorporate uncertainties in your recommendations?

In the final report about the case study, and in other dissemination material, we stress that these are the outcomes of model simulations and not predictions about future reality. We also stress that the climate scenarios are the most extreme from the current range and reality might be somewhere in the middle, or even beyond this range. In general, the managers involved understood really well the limitations of the approach, and how they should approach the results. They even explicitly asked about the uncertainties.

Which obstacles are limiting the implementation of adaptive management?

The Dutch Forest law currently does not recognise Tilia as a forest species. Large-scale plantations of Tilia are thus a violation of the Dutch forest law, but in practice this is tolerated by the inspectors.

Part of the current Natura2000-labelled old-growth oak and oak-beech sites would convert to Douglas fir forest under the more extreme climate scenario, and management will only partly be able to retard this conversion. To maintain the characteristic old-growth ground vegetation, conversion to Scots pine forest would be much more favourable than the spontaneous conversion to Douglas fir. Light conditions are much better under Scots pine. However, such a development is in conflict with the Natura2000 rules.